This week I’m returning to the samurai theme I started with my post about Shōgun (here) with some thoughts about an underrated hip-hop album from 2016: Ka’s “Honor Killed the Samurai”. I’ve always wanted to do a deep dive on this album, and by researching it I’ve learned more about New York City history, discovered a book on samurai practices in Japan, and considered what role, if any, honor should play in our modern society.

“Honor Killed the Samurai” has always been a special album to me. It came out in August the summer after I graduated college and I immediately appreciated how different it sounded than the trap-dominated music of that era. I’ve always admired the sound of Ka’s voice and vocal delivery, the way that he can almost whisper a lyric and let its meaning be the centerpiece is one of the many things that makes him unique. He is an artist confident enough to present his craft without superfluous gimmicks or novelty. When I write–especially in the earlier drafts of something–my lack of confidence can come through in the prose, I’m worried about what the audience might think of me so I avoid writing with strong, active sentences because I’m afraid to take ownership over my own ideas. In this post I’m going to try and take inspiration from Ka.

More specifically, writing this piece has pushed me as a writer. It’s two weeks later than when I planned to post it, and I spent between 3-4 hours every day for the better part of a month working on it (don’t take that as a guarantee that it will be good). I went back and forth on whether this should be my story to tell, what the implications were of writing about a neighborhood that I don’t live in, and whether my audience wanted to hear me write about music. Ultimately, I decided to go forward with it as an exercise in being brave and trying to own my ideas. I hit 50 subscribers on my last post and I feel very grateful, thank you all for supporting me. I hope you enjoy this.

Brownsville

“Space is everything”

-Ka in Passion of the Weiss

Brownsville Brooklyn is a neighborhood between Crown Heights, Bed-Stuy, and East New York. Historically Brownsville has been a home for the marginalized people of New York, originally Eastern-European Jews and then African-American families leaving the American South during the Great Migration. This neighborhood is the setting for “Honor Killed the Samurai” where Ka reminisces on his upbringing while declaring the person he wants to be moving forward.

The name Brownsville was created by a housing developer seeking to lure Jewish people away from the Lower East Side to a neighborhood with more space. The irony is that Brownsville became densely populated with families crammed into wooden tenement buildings, by 1950 Brownsville had the highest concentration of Jews living anywhere in America.

“Over Brownsville way housing conditions are bad. Sometimes six small children sleep in one bed in the more crowded and poorer sections.[...]In stuffy ill-smelling tenement sleeping rooms where no social service expert has been called, where there is income enough to hold aloof from proffered aid, there is an undreamed of spirit of womanhood.[...] Go out beyond the places where unkempt children sprawl on filthy pavements; where merchants shriek their wares; where there is squalor on the one hand and tawdry wealth on the other.”

-Brooklyn Daily Eagle 1921

During the 1950s Brownsville underwent a demographic change as black families began to move in after leaving the Jim Crow South and the US government put immigration quotas on Russian and Eastern European Jews. By the 1960s Brownsville was a predominantly black neighborhood, but it still carried with it a negative reputation from what came before.

I’ll give two examples. First is that before black families began moving into Brownsville, it had the reputation of being dangerous because of the “Murder Inc” gang. This was a group of contract killers for the Jewish and Italian mafias, and the gang was responsible for between 400 and 1,000 murders. Second is that Brownsville was a chemical dumping ground for the glue factories of Jamaica Bay, and as you’ll see later when Brownsville gets a reputation for being “derelict” much of that has to do with the fact that the land was blighted (environmentally contaminated) and couldn’t be developed according to New York City’s own housing codes.

Ka actually references this on the song “That Cold and Lonely”, “If not for Fresh Air Fund, I’da died in the smog”. The Fresh Air Fund is an organization that helps kids from the inner-city get out into the wilderness and the smog Ka is referencing is toxic fumes from the factories of Brooklyn.

The crack and heroin epidemics of the 1980s and 1960s (respectively) further cemented the reputation of Brownsville and were used as an explanation for the living conditions in the neighborhood. The influx of weapons used to protect drug territory and the escalation of the war on drugs caused Brownsville to be labeled the murder capital of New York City from the 1990s to the present.

There are two moments about Ka and Brownsville that I would like to put in conversation with each other. The first was in 1970 when New York City Mayor John Lindsay visited Brownsville. He was so appalled by the conditions that he referred to Brownsville as “Bombsville” because he said it looked like a bomb had gone off there. At this time Brownsville was dealing with the effects of tenements being destroyed to build low-income housing, poverty, and the effects of environmental damage, which all culminated in a string of arsons in Brownsville (as well as several important non-violent protests but those weren’t covered nearly as much).

The second moment was when the New York Post published this article about Ka, “FDNY Captain Moonlights as Anti-Cop Rapper”.

Space is everything. We all become who we are because of where we are, every human has to identify with someplace. When an outsider comes in and soapboxes the problems of your community it not only damages its reputation–which as we’ve seen time and time again can have material political consequences– but also can serve to distort your own understanding of the place that you live. This distortion is evident in the NY Post hit-piece; a mostly white and conservative audience is fed the narrative about the dangers of Ka, a civil servant, moonlighting as an “anti-cop rapper”. However, we can be somewhat grateful to the NY Post for telling us that Ka is a fire captain because I think it is important context, it’s the stakes, it proves he has skin in the game.

My point is that not only does learning about Ka teach us about where his music comes from, but also that there is power in narratives to distort how we think about something because of what stories catch on and are repeated and which ones aren’t.

Bushido

“These seconds, these minutes right here

You know who they belong to?

Us

That’s why they call ‘em ours

-Ka, “Ours”

Ka began his rap career in the early 90s when the underground hip-hop music scene in New York was flourishing. While Ka did not reach early commercial successes with the groups Natural Elements and Nightbreed, he has received critical and artistic acclaim putting him up there with Brownsville’s greatest MCs: a list that includes Sean Price (RIP), MOP, Smif-n-Wesson, several members of the Wu-Tang Clan, and Masta Ace.

In 2011 Ka’s album Iron Works made it’s way to GZA who featured Ka on his song Firehouse where Ka delivered three strong verses. The rest is history.

What makes Ka a great artist in my opinion is that his vision is singular. He produces all of his music so it sounds like him. There is no record label, or A&R to tell him whether he can or cannot release an album or what songs to put on it. He started out by mailing his CDs directly to people! His music is essential in the sense that all of the elements that aren’t needed are taken away.

“Fly rewards for my recordings, don’t stress the shine

Wrote the screenplay, direct, and set design

They writin’ deadlines, I ain’t pressed for time”

-Ka, Conflicted

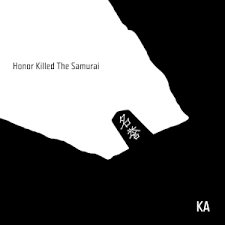

On “Honor Killed the Samurai” this singular vision is used to explore the concept of honor, and the way Ka does this is by talking about the samurai. As an audience, we know that the samurai died because of honor, this is evidenced by the album title and the artwork which depicts a grave from the perspective of someone buried in it looking up at a tombstone that reads (名誉) the Japanese characters for honor.

My working definition of honor is “adhering to what is right or to a conventional standard of conduct”, so then what is the value of honor to the samurai (or Ka) if it’s something that can get you killed? This, my friends, is the core conflict of the album.

On the chorus of “Conflicted” Ka raps,

“Mommy told me, ‘Be a good boy

Need you alive, please survive, you my hood joy’

Pops told me, ‘stay strapped son

You need the shotty, be a body or catch one’”

-Ka, “Conflicted”

Ka outlines two codes of conduct: surviving and being “a good boy” as prescribed by his mother who wants him to survive and presumably be a good person, and his father, who also presumably wants him to become a good person, but understands the need to protect himself in his unforgiving environment.

On the intros and outros of several songs we hear a female voice speaking about samurai, who they are and what they do. These samurai were warriors but also poets and musicians trained in the art of meditation, “The custom prevailed for young men to practice music in order that this gentle art might alleviate the rigors of that inclement region.”

These samples all come from a book “Bushido the Soul of Japan” written by Japanese educator and diplomat Nitobe Inazō in 1899. This book, written in English for a Western audience, is about samurai ethics, called Bushido, and Japanese culture. It became very popular in the West during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. In the book Nitobe writes of the seven samurai virtues: loyalty, rectitude, benevolence, courage, sincerity, politeness, and honor.

To be honorable, according to Nitobe, is to have a good name and that means defending one’s reputation even through means of violence.

By using an allusion to something outside of Brownsville, Ka creates a frame of reference for how we can compare him as a character to the samurais of Japan. Ka’s singular vision of putting together Brownsville and Samurai Japan, a narrative that he can manipulate and control, sets the stage for a broader discussion on the album of what it means to be honorable.

Space is everything so what it means to be honorable in Brownsville is necessarily different than what it means to be honorable in Japan. In “Honor Killed the Samurai” Ka raps about his younger self doing what he felt like he “had to” and how his older self has a more communitarian idea of honor. On “Just” we get the most clear reference to the Ka of the past,

“Trying to find a reason, I’m still alive breathin’

I wanna heal my inner child, it’s been a while grievin’

Ones dropped from cocked semis and clapped with the fours

Can’t remember none of my members gone from natural cause”

-Ka, “Just”

These four lines are important because they describe how honor has harmed Ka and his ‘members’. It is also a critique of violence by saying that growing up in Brownsville damaged Ka’s inner child (and likely others as well), and it is a call to action to find a different way forward. There has to be another reason to be alive breathing.

Ka continues to grapple with the idea of what honor means for him and his community throughout the album. Nowhere is this more clear than in his discussion of creating a blueprint for honorability on $,

“Watch me blueprint rec centers I’m tryin’ to inspire

I’ma blitz to get rich, feed alone starvin’

Give ‘em gift, how to fish, and seed they own garden

The right meals reveal destinations, life skills

Bless the next generation with bills, write wills

I need money, not for trivial material

Just to fix our flaws, the whole cause is ethereal”

By finding success, on his own terms, with his own vision, Ka has managed to stay true to himself and where he came from. The material rewards of that success mean that he can pour resources and blessings back into his community, thereby not only improving the material conditions of the people of Brownsville but also creating a new blueprint of what it means to be honorable.

Conclusion

While researching this album I came across another book called, “Why Honor Matters” by Tamler Sommers which argues that honor has been overlooked as a value in modern liberal societies in favor of dignity. Sommers argues that dignity societies focus on the individual and treating everyone the same, justice supposedly being blind is an example, whereas honor societies focus on how the actions of the individual can threaten or help the group. Honor has gotten a bad name because of revenge and glory, when someone thinks of honor they often think about dueling for example. However, honor can also mean accountability and using what you have for the collective good.

Every time I listen to “Honor Killed the Samurai” I am confronted with my own growth from a self-centered kid to an adult more focused on helping those around me. By putting the pain of his own childhood on display Ka is not only allowing himself to grieve his inner-child from the dangers he faced growing up, but transforming those struggles into a piece of art for his community and thus re-claiming the narrative of Brownsville. If space is everything, and who gets to take up space is political, then by creating art about his own place he is creating a home for others. That is what makes Ka a truly great artist. Thanks for reading.

-Luke

Ka is such an under-appreciated artist! I liked your contextualization of Honor Killed the Samurai.

If people want to dig deeper into his work, I recommend The Night's Gambit, Days with Dr. Yen Lo, or Descendents of Cain. (Also, if anyone has a hard time finding him by searching Ka, try searching BrownsvilleKa.)